Analysis of the poem "Vanity" by Birago Diop

Preview

We all have that African friend who sort of neglects nativity, roots and ties with this continent. Such people have their closet filled with designers (non African), their playlist of bereft of the afro pop sound, their dishes are 'from abroad', they would never be caught dead in their natural hair, it has to be straightened.... And many more 'I ain't feeling Africa' attitude.

These are the set of people the poet throws (or threw) caution in the wind for. Though written as far back as the colonial era, when Africa was still regarded as the dark continent, it's relevance in today's day to day living can not be over emphasised. The poetic voice takes on that of a prophet, predicting the downfall of the African culture if the citizens decide to neglect it's roots and embrace another. Especially that culture that makes mockrey of who they are.

Settings

The physical setting of this poem cannot be determined from the poem itself, but it is very safe for us to just say Africa, considering the situational and time setting of the poem and of course the poet. The poem was written during the colonial period when Africa was still under the tight shackles of the colonial masters. For the areas colonized by the French mas ters, they were under the system of assimilation. The high and low of this system was; the French were after making a Frenchman out of the people under their colonies. It was a sort of rebirth: they were to learn the French language and follow the French principles of life. It was like trying to turn an orange into a tangerine. This was the situation when this poem was written. The time, obviously was the colonial period, but we can see for ourselves the relevance of this poem several decades after it was written.

Structure

The poem is written in 30 lines, which are further divided into 5 unequal stanzas. Each with its own message.

1st stanza has 5 lines

2nd stanza also has 5 lines

3rd stanza has 4 lines

4th stanza which is the longest has 10 lines

The last stanza has 6 line..

The summary of each stanza is quite significant if the whole message is to be fully captured. As we all know that poets have a way of making you want to rack your brain like you are a victim of quantum physics. This poem does not distinctively point at preservation of culture as the message, but as you delve deeper into the lines you begin to note certain indications of what the poet tries to communicate.

The first three stanzas are clear warnings of things that might happen in future. The poem at this stanzas is replete with rhetorical questions and if's, if you are an African child you would know well enough the significance of rhetorical questions in a parent's tirade. Thus we can compare this poem to a sort of tirade by a statesman, who as an elderly, sees that which a child cannot see while standing, on his seat, over a piece of paper and a dancing pen.

A closer attention should be drawn to the second stanza where the poet makes mention of 'big children' whose laughter has shaped their mouths into a very large one. This is a comical and well metaphored description of the the relationship between the white masters and the colonized Africans: an imposition of lifestyle on a set of people by others who deem it their job and personal business to see to the 'shaping' and reshaping of a lifestyle they consider low standard.

The third stanza also refers to this problem as a sort of tumour, a cancerous infection spreading across the width of the society. He cannot be more near to the truth as this observation is given credence to by the situation in the continent today. A neglect of the African way of life is becoming a trend or more accurately, has become a trend taking it's roots at an alarming rate.

The fourth stanza has the poet taking us back to the warnings of the ancestors. Of course we all know that the ancestors are never resting in the African setting they still take our sacrifices and speak through messengers. Though they are referred to as 'dead' they are still very much speaking, but note, 'with clumsy voices' (this is some whole real horror movie'). Coupled with the clumsiness in their voices is 'our' deafness, as such that their voices are not clear enough, neither is our ears responsive to the voices in the first place, this their message doesn't even get to the intended recipient. The poet's mood is that of anger at this point and we can almost feel his hard scribbling on the poor paper, he tags the recipients as not only deaf but also 'blind and unworthy'

The fifth, and last stanza comes off as a fed up, resigning point for the poet, he sees this situation as a lost cause because no one is listening, and at the end no one would listen to the cries of the African 'son' who has forgotten the roots of his existence. This is also getting closer to reality... People like the present POTUS who does not hide the fact that the world is getting tired of the African problems and the developed world would sooner or later leave the just crawling developing countries to fend for themselves, but not before exploiting and shaping them into 'ugly', 'large mouthed' people.

Figures of speech/ techniques

Rhetorical questions: the poet makes use of rhetorical questions to "the fullest maximum"(I had to fhalz that one). The first three stanzas especially, are replete with questions to ponder on for the African sons and daughters. His use of these figure of speech is deep rooted in the African way of castigating a child. You are not told what you have done, but when the elders start to empty their barrage of questions on you, your brain clicks immediately. This is a very efficient way the poet employs to pass his message as an African elder. The summary of these questions is that if Africans continue to watch as their culture moves into extinction, while they in their habit continue to talk and cry without action who will offer help (especially when they are not surrounded by well meaning neighbours.)

Repetition: This is another effective way of preaching his message of a foreseeable doom. This technique can be likened to a blacksmith with an anvil and hammer, continuously hitting a point to get a desired result. The wordsmith here repeats certain words and phrases to drive home his message. Let's check lines 8 and 10, lines 6 and 28, lines 11 and 29, the repetitions here are rhetorical questions to remind Africans of the danger of believing they are that younger children whose needs and cries would be attended to by doting parents. Most African poems do not usually have the rhymes and constant rhythm, but that does mean they cannot have a musical feel and that is where repetition comes in, for other repetitions e.g. lines 1 and 27, they give the poem a musical feel.

Synecdoche: a lot of body parts are used to represent the African citizenry, especially the senses. This in its own way is at some points comical and at the same time pinching: take for example where the poet makes mention of "our large mouths" that is something to laugh about especially with a Snapchat-pictures-aided imagination, but taking a deeper thought, we find the poet's attempt to describe the dilemma of the African continent in the hands of neo-colonial masters in the guise of saviours who view our problems as a comedy show. It can be deduced that the poet also tries to appeal to our senses, tries to touch the very core, and sensitise Africans against "westernising" themselves as the end result is disaster.

Conditional clause: many of the rhetorical questions are preceded by the conditional word "if". This technique has a two sided effect: one is that it tells of the probability that things might be go wrong as Africans continue to neglect their roots, and on the second side it presents hope that it might not have happen. But for the latter, the lost sons and daughters would have to open their ears to "clumsy voices" of "their dead" (what a solution 😒).

Humour: Birago Diop sure has a lot of sacarsm and humour up his sleeve, (or perhaps we say pen) he sort of roasts everyone under the radar with his deft use of humour. We can continue laugh at "large mouth" or make fun of "complaining voices of beggers" untill we actually realise the joke is on us. Perhaps that only strikes in in the 4th stanza where the poet takes out all his anger to hit the nail on the head and calls "us, blind, deaf and unworthy Sons" here we know he's not trying to do stand up comedy. And remorse starts to set in.

Language/Diction: the poet's choice of words and the manner in which he articulates his message is a funny mix of simplicity and complexity. His diction is quite clear, simple without need for an encyclopedia. But, this simplicity does not guarantee the clarity of the figurative/deeper meaning of this poem. The language is sacarstic, the poet throwing shades at the unyielding sons, however we find a hint of pleading and hope.. Overall, the poet achieved satire with these two tools

Tone: the tone is also a mix as reflected by the language and diction. The poet's tone is that of despair, frustration, anger and a little drop of hope.

Themes.

Forgetting our roots.

This is a thing of very great concern, for Africa of then, now and tomorrow. After the colonial masters took over the reins of governing from the fore fathers, they tried to overhaul the lives of those under their rule, this was wrong and unfair, but since the end of colonialism, Africans seem to be finding it hard to find their way back to the roots. Suits, ties, gowns, jeans etc has replaced African prints, our palmwine sems to have lost its value in the face of vodka, Hennessy and the likes, our media isn't doing well enough, radio stations would rather "jam" foreign songs since that what the youth culture embraces, no more deep African beats tones and poignant lyrics (not the tin can and stones some artistes churn out these days though). It is very sad that we have to dump our own being, our essence and heritage because some people do not understand it and laugh at it. Who we are cannot be changed, we only continue to hurt ourselves and destroying our esteem by pulling away. This is one of the point of concern of the poet which he spells out in this poem.

The effect of the colonial rule on the African continent.

Even years after the white masters have loosened their reins on the continent, the effect of their coming in the first place still remains. For one, Africans have been made to see their culture as backward, something unpleasant to the aesthetic mind, "ugly" . They have shaped the life of their colonials into something they see as superior, and by extension, relegating their (colonials) culture and consequently self esteem. But in the same vein, some people like the poet here who have seen the highs and lows of the culture of the colonial masters, have discovered that, it is merely a case of cultural differences and not necessarily superiority: in fact, these colonial masters have been through bad times of epidemics, despotic rulers and being barbarians themselves. Thus the reason for him (the poet) writing this so as to cure the people of the not-too-good effects of the colonial masters in their African colonies.

The importance of the ancestors

African ancestors are perhaps the most hardworking in the world, they are committed to overseeing day to day activities of their succeeding generations. They still speak, but unfortunately with clumsy voices. The poet hints the issue of generational gap in his point at this stage (stanza 10), and this is similar to the way children now find it difficult understanding their parents and their parents understanding them. The same applies to "our dead" and "us", "their voices" are "clumsy" just as our ears are deaf , but, necessarily not because it's really clumsy or we are deaf, but because a generational gap has been created, (thanks to you colonial rulers). The older generations stick to the traditions, but the younger generation are wont to pulling away towards the new culture, thus there's is a gap. The poet here tries to serve a bridge between the old and young as the wisdom of the elderly cannot be placed aside without we bearing certain consequences.

Hope for a future

Even though the tone of the poet is that of anger, pain and displeasure, it still portrays a hint of hope, a foreseeable change it and only if Africans admit, and acknowledge their misdoings and effect the change. Fortunately, this hope is coming to light as a AFRO movement is becoming something big. People like Chimmamanda Adichie are bringing back the essence of the African culture in terms of promoting African prints, the kinky African hair as a normality, designers in the African continent are promoting African styles. This is quite good but not the best, perhaps when we have our leaders and workers not reserving native attires for Friday then we can say we are there.

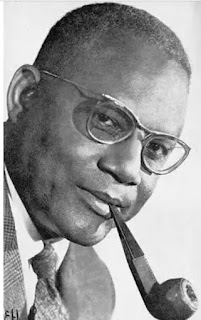

Meet the poet, Birago Diop.

Birago Ismaël Diop was born 11 December 1906 in Oukam, Dakar. He attended Lycée Fudherbe in St Louis, then moved on to the University of Toulouse in France to study veterinary medicine and graduated in 1933.

His educational journey exposed him to works of great minds in the literary world. The likes of Victor Hugo, Edgar Allan Poe, influenced him a great deal, also, the locals where he served as a government castle inspector tickled his inspiration with their wealth of folktales and traditional stories.

He has several works in different genres: traditional folktales, poetry, drama. Another of his poems is "Lures and Glimmers". He authored several narratives like TALES OF AMADOO, NEW TALES OF AMADOO, TALES AND COMMENTARY.

Vanity

If we tell, gently, gently

All that we shall one day have to tell,

Who then will hear our voices without laughter,

Sad complaining voices of beggars

Who indeed will hear them without laughter?

If we cry roughly of our torments

Ever increasing from the start of things

What eyes will watch our large mouths

Shaped by the laughter of big children

What eyes will watch our large mouth?

What hearts will listen to our clamoring?

What ear to our pitiful anger

Which grows in us like a tumor

In the black depth of our plaintive throats?

When our Dead comes with their Dead

When they have spoken to us in their clumsy voices;

Just as our ears were deaf

To their cries, to their wild appeals

Just as our ears were deaf

They have left on the earth their cries,

In the air, on the water,

where they have traced their signs for us blind deaf and unworthy Sons

Who see nothing of what they have made

In the air, on the water, where they have traced their signs

And since we did not understand the dead

Since we have never listened to their cries

If we weep, gently, gently

If we cry roughly to our torments

What heart will listen to our clamoring,

What ear to our sobbing hearts

Preview

We all have that African friend who sort of neglects nativity, roots and ties with this continent. Such people have their closet filled with designers (non African), their playlist of bereft of the afro pop sound, their dishes are 'from abroad', they would never be caught dead in their natural hair, it has to be straightened.... And many more 'I ain't feeling Africa' attitude.

These are the set of people the poet throws (or threw) caution in the wind for. Though written as far back as the colonial era, when Africa was still regarded as the dark continent, it's relevance in today's day to day living can not be over emphasised. The poetic voice takes on that of a prophet, predicting the downfall of the African culture if the citizens decide to neglect it's roots and embrace another. Especially that culture that makes mockrey of who they are.

Settings

The physical setting of this poem cannot be determined from the poem itself, but it is very safe for us to just say Africa, considering the situational and time setting of the poem and of course the poet. The poem was written during the colonial period when Africa was still under the tight shackles of the colonial masters. For the areas colonized by the French mas ters, they were under the system of assimilation. The high and low of this system was; the French were after making a Frenchman out of the people under their colonies. It was a sort of rebirth: they were to learn the French language and follow the French principles of life. It was like trying to turn an orange into a tangerine. This was the situation when this poem was written. The time, obviously was the colonial period, but we can see for ourselves the relevance of this poem several decades after it was written.

Structure

The poem is written in 30 lines, which are further divided into 5 unequal stanzas. Each with its own message.

1st stanza has 5 lines

2nd stanza also has 5 lines

3rd stanza has 4 lines

4th stanza which is the longest has 10 lines

The last stanza has 6 line..

The summary of each stanza is quite significant if the whole message is to be fully captured. As we all know that poets have a way of making you want to rack your brain like you are a victim of quantum physics. This poem does not distinctively point at preservation of culture as the message, but as you delve deeper into the lines you begin to note certain indications of what the poet tries to communicate.

The first three stanzas are clear warnings of things that might happen in future. The poem at this stanzas is replete with rhetorical questions and if's, if you are an African child you would know well enough the significance of rhetorical questions in a parent's tirade. Thus we can compare this poem to a sort of tirade by a statesman, who as an elderly, sees that which a child cannot see while standing, on his seat, over a piece of paper and a dancing pen.

A closer attention should be drawn to the second stanza where the poet makes mention of 'big children' whose laughter has shaped their mouths into a very large one. This is a comical and well metaphored description of the the relationship between the white masters and the colonized Africans: an imposition of lifestyle on a set of people by others who deem it their job and personal business to see to the 'shaping' and reshaping of a lifestyle they consider low standard.

The third stanza also refers to this problem as a sort of tumour, a cancerous infection spreading across the width of the society. He cannot be more near to the truth as this observation is given credence to by the situation in the continent today. A neglect of the African way of life is becoming a trend or more accurately, has become a trend taking it's roots at an alarming rate.

The fourth stanza has the poet taking us back to the warnings of the ancestors. Of course we all know that the ancestors are never resting in the African setting they still take our sacrifices and speak through messengers. Though they are referred to as 'dead' they are still very much speaking, but note, 'with clumsy voices' (this is some whole real horror movie'). Coupled with the clumsiness in their voices is 'our' deafness, as such that their voices are not clear enough, neither is our ears responsive to the voices in the first place, this their message doesn't even get to the intended recipient. The poet's mood is that of anger at this point and we can almost feel his hard scribbling on the poor paper, he tags the recipients as not only deaf but also 'blind and unworthy'

The fifth, and last stanza comes off as a fed up, resigning point for the poet, he sees this situation as a lost cause because no one is listening, and at the end no one would listen to the cries of the African 'son' who has forgotten the roots of his existence. This is also getting closer to reality... People like the present POTUS who does not hide the fact that the world is getting tired of the African problems and the developed world would sooner or later leave the just crawling developing countries to fend for themselves, but not before exploiting and shaping them into 'ugly', 'large mouthed' people.

Figures of speech/ techniques

Rhetorical questions: the poet makes use of rhetorical questions to "the fullest maximum"(I had to fhalz that one). The first three stanzas especially, are replete with questions to ponder on for the African sons and daughters. His use of these figure of speech is deep rooted in the African way of castigating a child. You are not told what you have done, but when the elders start to empty their barrage of questions on you, your brain clicks immediately. This is a very efficient way the poet employs to pass his message as an African elder. The summary of these questions is that if Africans continue to watch as their culture moves into extinction, while they in their habit continue to talk and cry without action who will offer help (especially when they are not surrounded by well meaning neighbours.)

Repetition: This is another effective way of preaching his message of a foreseeable doom. This technique can be likened to a blacksmith with an anvil and hammer, continuously hitting a point to get a desired result. The wordsmith here repeats certain words and phrases to drive home his message. Let's check lines 8 and 10, lines 6 and 28, lines 11 and 29, the repetitions here are rhetorical questions to remind Africans of the danger of believing they are that younger children whose needs and cries would be attended to by doting parents. Most African poems do not usually have the rhymes and constant rhythm, but that does mean they cannot have a musical feel and that is where repetition comes in, for other repetitions e.g. lines 1 and 27, they give the poem a musical feel.

Synecdoche: a lot of body parts are used to represent the African citizenry, especially the senses. This in its own way is at some points comical and at the same time pinching: take for example where the poet makes mention of "our large mouths" that is something to laugh about especially with a Snapchat-pictures-aided imagination, but taking a deeper thought, we find the poet's attempt to describe the dilemma of the African continent in the hands of neo-colonial masters in the guise of saviours who view our problems as a comedy show. It can be deduced that the poet also tries to appeal to our senses, tries to touch the very core, and sensitise Africans against "westernising" themselves as the end result is disaster.

Conditional clause: many of the rhetorical questions are preceded by the conditional word "if". This technique has a two sided effect: one is that it tells of the probability that things might be go wrong as Africans continue to neglect their roots, and on the second side it presents hope that it might not have happen. But for the latter, the lost sons and daughters would have to open their ears to "clumsy voices" of "their dead" (what a solution 😒).

Humour: Birago Diop sure has a lot of sacarsm and humour up his sleeve, (or perhaps we say pen) he sort of roasts everyone under the radar with his deft use of humour. We can continue laugh at "large mouth" or make fun of "complaining voices of beggers" untill we actually realise the joke is on us. Perhaps that only strikes in in the 4th stanza where the poet takes out all his anger to hit the nail on the head and calls "us, blind, deaf and unworthy Sons" here we know he's not trying to do stand up comedy. And remorse starts to set in.

Language/Diction: the poet's choice of words and the manner in which he articulates his message is a funny mix of simplicity and complexity. His diction is quite clear, simple without need for an encyclopedia. But, this simplicity does not guarantee the clarity of the figurative/deeper meaning of this poem. The language is sacarstic, the poet throwing shades at the unyielding sons, however we find a hint of pleading and hope.. Overall, the poet achieved satire with these two tools

Tone: the tone is also a mix as reflected by the language and diction. The poet's tone is that of despair, frustration, anger and a little drop of hope.

Themes.

Forgetting our roots.

This is a thing of very great concern, for Africa of then, now and tomorrow. After the colonial masters took over the reins of governing from the fore fathers, they tried to overhaul the lives of those under their rule, this was wrong and unfair, but since the end of colonialism, Africans seem to be finding it hard to find their way back to the roots. Suits, ties, gowns, jeans etc has replaced African prints, our palmwine sems to have lost its value in the face of vodka, Hennessy and the likes, our media isn't doing well enough, radio stations would rather "jam" foreign songs since that what the youth culture embraces, no more deep African beats tones and poignant lyrics (not the tin can and stones some artistes churn out these days though). It is very sad that we have to dump our own being, our essence and heritage because some people do not understand it and laugh at it. Who we are cannot be changed, we only continue to hurt ourselves and destroying our esteem by pulling away. This is one of the point of concern of the poet which he spells out in this poem.

The effect of the colonial rule on the African continent.

Even years after the white masters have loosened their reins on the continent, the effect of their coming in the first place still remains. For one, Africans have been made to see their culture as backward, something unpleasant to the aesthetic mind, "ugly" . They have shaped the life of their colonials into something they see as superior, and by extension, relegating their (colonials) culture and consequently self esteem. But in the same vein, some people like the poet here who have seen the highs and lows of the culture of the colonial masters, have discovered that, it is merely a case of cultural differences and not necessarily superiority: in fact, these colonial masters have been through bad times of epidemics, despotic rulers and being barbarians themselves. Thus the reason for him (the poet) writing this so as to cure the people of the not-too-good effects of the colonial masters in their African colonies.

The importance of the ancestors

African ancestors are perhaps the most hardworking in the world, they are committed to overseeing day to day activities of their succeeding generations. They still speak, but unfortunately with clumsy voices. The poet hints the issue of generational gap in his point at this stage (stanza 10), and this is similar to the way children now find it difficult understanding their parents and their parents understanding them. The same applies to "our dead" and "us", "their voices" are "clumsy" just as our ears are deaf , but, necessarily not because it's really clumsy or we are deaf, but because a generational gap has been created, (thanks to you colonial rulers). The older generations stick to the traditions, but the younger generation are wont to pulling away towards the new culture, thus there's is a gap. The poet here tries to serve a bridge between the old and young as the wisdom of the elderly cannot be placed aside without we bearing certain consequences.

Hope for a future

Even though the tone of the poet is that of anger, pain and displeasure, it still portrays a hint of hope, a foreseeable change it and only if Africans admit, and acknowledge their misdoings and effect the change. Fortunately, this hope is coming to light as a AFRO movement is becoming something big. People like Chimmamanda Adichie are bringing back the essence of the African culture in terms of promoting African prints, the kinky African hair as a normality, designers in the African continent are promoting African styles. This is quite good but not the best, perhaps when we have our leaders and workers not reserving native attires for Friday then we can say we are there.

Meet the poet, Birago Diop.

Birago Ismaël Diop was born 11 December 1906 in Oukam, Dakar. He attended Lycée Fudherbe in St Louis, then moved on to the University of Toulouse in France to study veterinary medicine and graduated in 1933.

His educational journey exposed him to works of great minds in the literary world. The likes of Victor Hugo, Edgar Allan Poe, influenced him a great deal, also, the locals where he served as a government castle inspector tickled his inspiration with their wealth of folktales and traditional stories.

He has several works in different genres: traditional folktales, poetry, drama. Another of his poems is "Lures and Glimmers". He authored several narratives like TALES OF AMADOO, NEW TALES OF AMADOO, TALES AND COMMENTARY.

Comments

Post a Comment